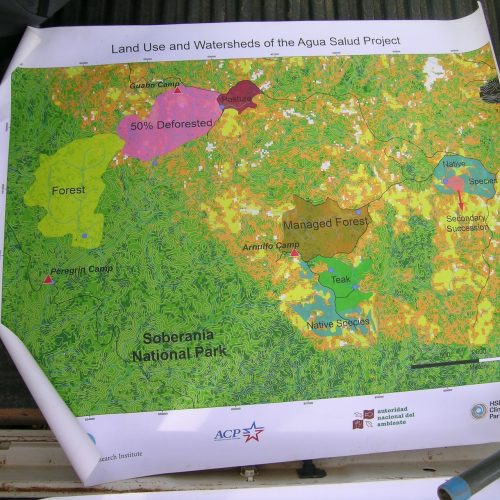

“The Panama Canal Watershed is perhaps one of the tropics’ clearest examples of ecosystem services in action. The basin’s fresh water transports four percent of seafaring world trade, generates $2.5 billion in annual revenue and sustains one of the fastest growing economies in the world today. Named for the Agua Salud River, the 700-hectare Panama Canal Watershed Project seeks to explain how different landscapes common in the rural tropics — from intact forests to cattle ranches — impact ecosystem services in an era of exploding population growth, ecosystem degradation, and global climate change.” (STRI Website)

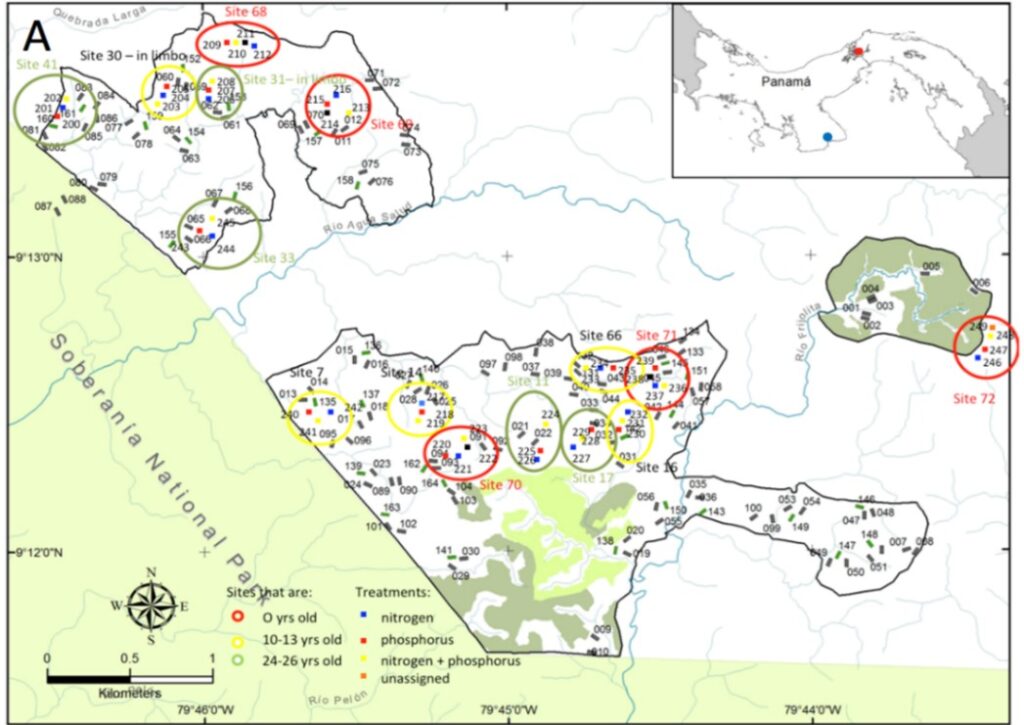

Map of the Agua Salud area with all major vegetation studies. The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute manages the delineated areas. Dark-green-shaded area indicate the 60 ha mixed-species reforestation experiment, light-green shaded areas an experimental teak plantation, the numbered rectangular symbols individual 0.1 ha plots, including the 108 core SFD study plots, the liana removal plots and the fertilization plots. The layout of the latter experiment is highlighted. The red dot in the smaller map indicates the principle location of the Agua Salud study within Panama, while the blue dot indicates the location of the studies’ dry tropical component, with 26 standard SFD plots plus 13 liana removal plots.

Team

Overview

As postdoc at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, I set up a secondary forest research component within the framework of the larger Agua Salud Project on ecosystem services of different land-uses. I wanted to set up a study system for the study of local but also landscape-scale drivers of succession (e.g., dispersal limitation), which would help us to investigate what drives spatial variation in the dynamics of successional plant communities.

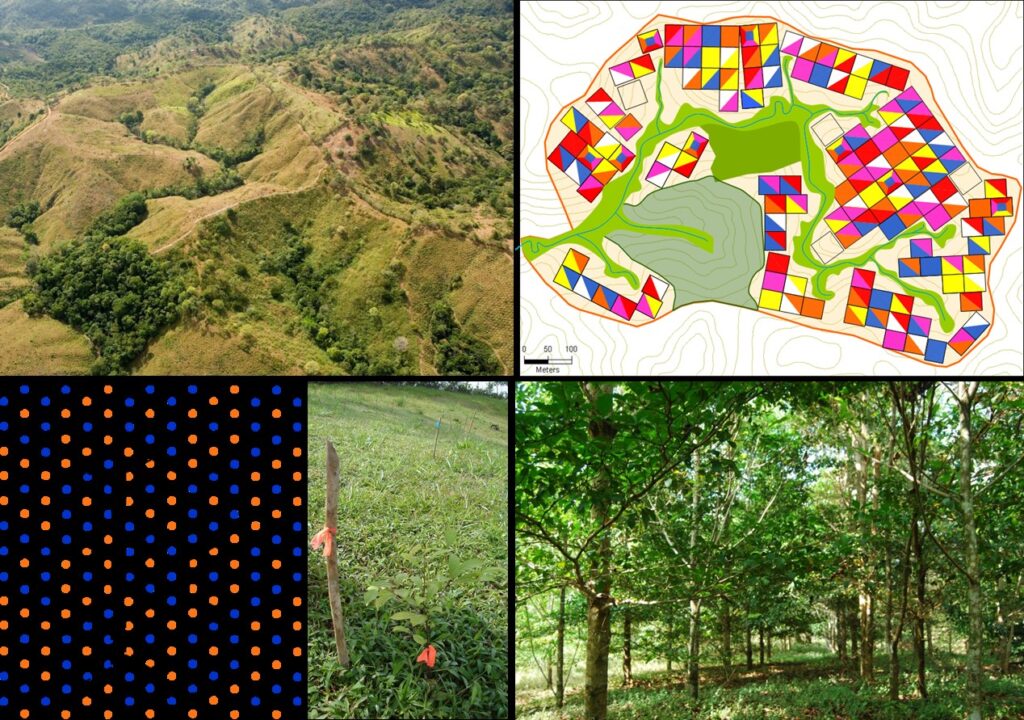

To this end, I designed a longitudinal study with a spatial sampling design with local contrasts in topography and connectivity, nested within a highly replicated landscape-scale sampling of forests in narrow age classes. The design has a few features that are, to my knowledge, unique among existing long-term secondary forest studies. 54 secondary forest locations were randomly selected within the Agua Salud landscape and within age-classes, ensuring that (i) the study locations represented an unbiased age-stratified sample of the variation in soil, landscape context and land-use history across the landscapes, as well as in forest structure and composition, and (ii) that we had replication of plots within age classes.

The field studies in Panama are meant to be maintained for at least another decade – and hopefully more.

Dispersal limitation and secondary forest succession

An unique feature of my research on secondary forest succession is its focus on ecological succession as a result of processes at the local (e.g. competition) and the landscape scale (e.g., dispersal). This focus is possible because of how I set up my field site in Panama: a longitudinal study with a spatial sampling design with local contrasts in topography and connectivity, nested within a highly replicated landscape-scale sampling of forests in narrow age classes. Key findings of my work are that (i) a trade-off between dispersal limitation and shade tolerance cause variation in the rates at which species recruit into and disappear from the plant community, driving predictable local and landscape-scale patterns of species shifts over the course of succession. At the same time, (ii) dispersal limitation and spatial heterogeneity in soil resources are important drivers of the observed variation in the composition of plant communities at local and landscape scales. (iii) The relative strength of these two ecological processes changes with scale, landscape-context and successional age of the forest.

Vegetation Removal Experiments

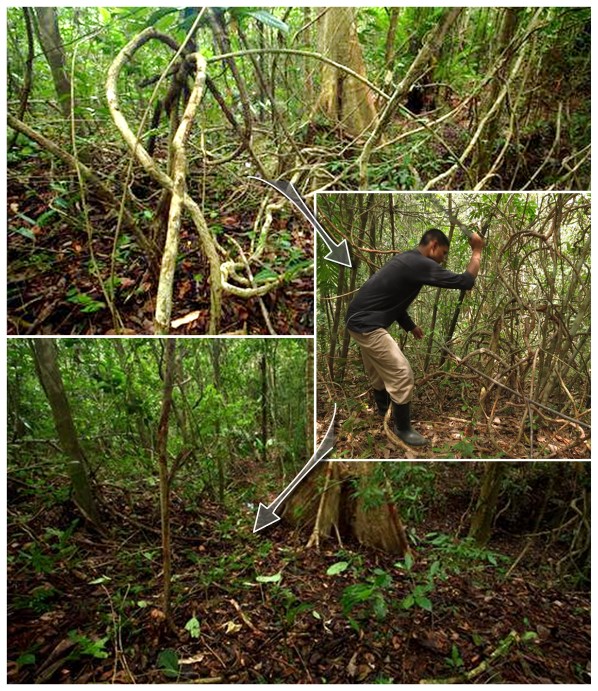

Collaborators and I have set up two long terms studies that involve the manipulation of naturally regenerating secondary forests. This experiment seeks to understand how lianas affect the dynamics, productivity and succession of the plant communities in early secondary forests and adds one vegetation plot to 30 of our 54 secondary forest locations from which all lianas are eliminated.

Lianas turned out to indeed strongly reduce tree biomass growth, but in contrast to what was previously thought, this effect was weaker in young than in old secondary forests. An experimental follow-up provided nuance, as it showed that the per-capita effect of lianas remains constant during succession under similar liana infestation levels for the canopy trees.

Diversity change and stability of forest growth along a successional gradient

Using a chronosequence approach, I have found high rates of recovery of biomass and tree species diversities during the first three decades of succession in moist tropical forests in Mexico and Panama, and much lower rates of recovery in a dry tropical forests in Panama. Species composition, however, recovered at a much slower pace, with even the oldest sites being very different form nearby old-growth forests.

The formation of the 2ndFor network with over 40 chronosequence studies from across tropical South and Central America, three of which I have contributed, has made it possible to assess how the rate of forest recovery varies along large-scale environmental or geographical gradients. In a range of studies, we found vast differences in the recovery rates of biomass, biodiversity, and functional diversity. These differences could partly be explained by differences in rainfall patterns, with an additional weak soil effect. These results also confirmed the generality of the observation that while biomass and species diversity may recover within a few decades, it takes centuries for species composition to recover, if it ever does.

Succession of soil microbial communities

With molecular ecologist Dr. Kristin Saltonstall and Dr. Jeff Hall, I investigate if and how the soil microbial community recovers during forest succession in a moist and a dry tropical region in Panama. Results suggest a clearer trajectory of recovery in the moist region, with interesting differences between the moist and dry tropical region in their recovery of functional diversity.

Collaborators